The Naval Corps Flanders (Marine–Korps Flandern) was operable throughout the entire First World War (1914-1918). The naval corps was part of the German empire’s military forces and was stationed near the Flemish coast, ranging from the Dutch border to the Yser river. Soldiers of this Naval corps were not only active at sea but also on land and in the air.

The plan to send a naval corps to the Flemish coast in Belgium, was originally suggested by the German state secretary Von Tirpitz. It mainly consisted of ‘leftover’ units such as reserve troops. Originally, he assigned a defensive position to the division rather than an offensive position. De founding of the division took place on august 23rd 1914. It was led admiral Ludwig von Schröder, a 60-year old veteran who was actually already retired. Von Schröder had his own convictions with regard to the role of the naval corps in Flanders, and diligently proceeded to take matters into his own hands. He immediately took over the cities of Bruges and Zeebrugge as new bases.

To the coast of Flandres

When it was founded, the naval corps consisted of more than 10.000 men from various different divisions from Kiel and Wilhelmshaven. Before they fought along the Flemish coast, the soldiers fought in the Battles of Leuven, Antwerp and Mechelen and subsequently occupied Bruges, Zeebrugge and Ostend. The German army was halted near the Yser river, where the Allied forces had occupied a small stroke of land nearby the coastal line, north of the Yser river. Moreover, later on in the war the naval corps would also fight battles which were located far away from the coast lines.

Merging naval divisions

In the Flemish coastal region, the infrastructure including canals, bridges, locks and ports, as encountered by the Germans was still completely intact. Immediately they started building coastal defense batteries in order to defend themselves from sea based attackers. After the general German invasion of Belgium stagnated and turned into a trench war, reinforcements in the coastal area, and expansions with regard to the infrastructure, including docks and other buildings in the ports, gained more attention from the army command. Moreover, the naval division was responsible for these specific aspects and therefore indirectly gained more attention as well. In November 1914 the division merged with a second naval division and became the new Naval Corps Flanders (Marine–Korps Flandern). A third division, which contained among other things hussars and field artillery, was added on June 1st 1917.

Headquarters

The Naval Corps Flanders (Marine–Korps Flandern) was assigned to a approximately 60 kilometers long strip of coastal line ranging from the Dutch border to opening of the Yser river. In the middle of this area, approximately 12 kilometers inland, the city of Bruges was located. Bruges is connected to Zeebrugge, Ostend and the North Sea through canals. The army command was stationed in Bruges and after the spring of 1917 the most important wharf was also located here. Its location was based on strategic importance; near the English Channel, Great-Britain and the opening of the river Thames.

An increase in equipment

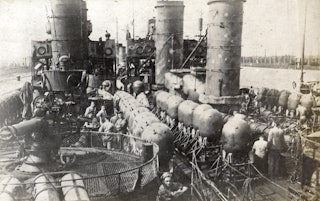

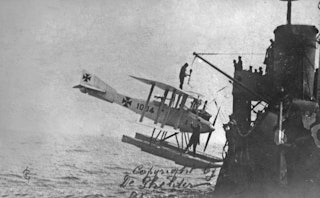

The ports and canals were due to their lack of depth only fit for smaller torpedo boats and submarines. Air support was essential in order to maintain the functionality of the naval units. This was also applicable to the coastal artillery batteries, who would adjust their fire in accordance to the pilots’ intel, once Allied forces increasingly started using smoke screens. A new developments in this process, was the use of radios which provided the receiver and the sender of information with a wireless connection and improved communications.

The firepower at sea increased when three destroyers were added to the naval corps following march 2nd 1916. They aimed to destroy as much enemy cargo ships as possible and consequently to cause starvation in Great-Britain. They were operable near the English eastern coastal region, the English Channel, the French western coastal area, the Bay of Biscay and the southern part of the Irish sea. The area was split up in quadrants, which were each assigned to a different submarine. In the Spring of 1915 Germany’s strategy involved unrestricted submarine warfare; all Allied ships including merchant vessels and passenger lines were under attack. Germany stopped employing this strategy however, in fear of provoking the Americans and consequent American involvement in the war. Nevertheless, on February 1st 1917 Germany started using the unrestricted submarine warfare tactics again.

A monkey as mascot

The naval corps’ mascot was a monkey. One of the naval corps’ photographs features a monkey, dressed in a jacket which was part of the German parade uniform and more commonly known as an ‘affenjacke’. The monkey also wears a sailors hat with the inscription ‘torpedo’. In addition to this photograph, Arend Mijs’ collection contains two other pictures, in which a sailor poses with a stuffed animal in the shape of a monkey. Moreover, the walls of a naval casino in Bruges, which was part of the nightlife facilities for the sailors, were decorated with paintings, some of which depicting monkeys as well. These murals showed monkeys while drinking champagne.

Furthermore, the future glossy photographer Erwin Blumenfeld (1897-1969) described his service time in the German army during WWI in his autobiography. For a short period of time, he was stationed with a motorized column which was deployed in Bruges. His division concerned itself with robbery and black market activities. Cargo freight wagons filled with provisions were opened at night, its contents were partially eaten and partially sold. When he halfheartedly decided to desert from the army and went to the Netherlands, he finds himself in conversation with a non-commissioned officer of the military police in a train towards the Dutch border. The officer tells him that the black market trade is organized in Sas van Gent. “I don’t have to tell you anything about these matters: your division is nicknamed the ‘champagnekolonne’ (the champagne column), the ‘dievenbende’ (den of thieves) for a reason!” (“ Ik hoef jou niks te vertellen over die reuzenzaken: die kolonne van jou heet niet voor niets de champagnekolonne, de dievenbende!”) [1]

The name of a specific part of the defense line near the coastal line probably also referred to the mascot. The German observation post in the high dune top near Lombardsijde was named the ‘Affenberg’ (Monkey Hill).

At sea

De duikboten van het Marinekorps Flandern werden geduchte vijanden van de geallieerde schepen. Het aantal Duitse duikboten nam tijdens de oorlog toe. De eerste onderzeeboot in de haven van Zeebrugge arriveerde in november 1914. In maart 1915 volgde de oprichting van de U-Bootflotille Flandern. Het flotille werd in oktober 1917 in twee afdelingen gesplitst. Beiden brachten tijdens de oorlog 2554 schepen tot zinken. Tachtig onderzeeboten gingen daarbij verloren, inclusief 145 officieren en meer dan 1000

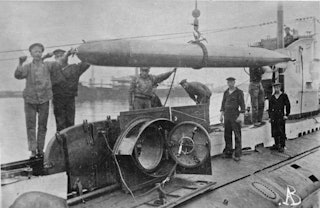

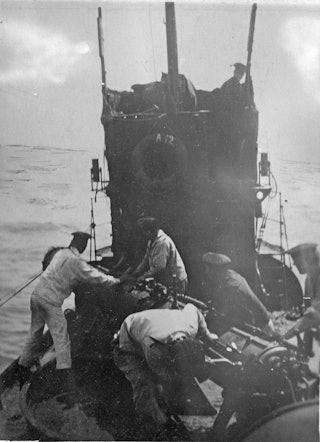

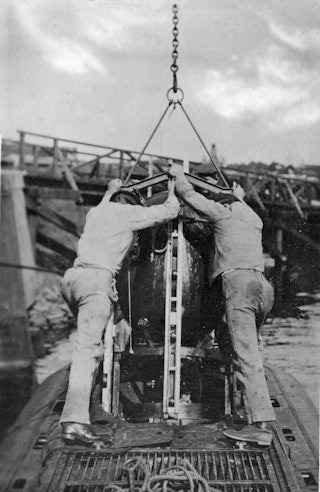

The submarines of the ‘Marine–Korps Flandern’ became infamous enemies of the Allied ships. The amount of German submarines increased during the war. The first submarine in the port of Zeeburgge arrived in November 1914. In March 1915 the ‘U-boat flotilla Flandern’ was created. The flotilla was split up in two divisions in October 1917. During the war approximately 2554 ships were sunk by the combined efforts of these U-boat flotillas. Eighty submarines were lost, including 145 officers aboard and over 1000 crewmembers.

The first submarines could not stay submerged in the water for long periods of time. Moreover, they were equipped with a limited amount of torpedoes. There were several different types of submarines; some could fire torpedoes and place sea mines, others could only fire torpedoes.

Initially Allied cargo ships and passenger ships would not always get torpedoed. The German submarines used to try and stop the ships by sailing above water level while signaling the ships with flags. Then the crew members of the Allied ship would get the opportunity to get into the sloops. Crewmembers of the submarine would bring explosives or flammable cargo aboard the Allied ship, which would cause it to sink. The people in the sloops would get towed and brought back to shore or nearby fishing vessels by the submarine.

The British responded by equipping their small fishing boats with weaponry. If a submarine was within range, they would fire at them. As a consequence, the Germans changed strategies and started to attack fishing boats and other small vessels as well.

Torpedo boats and destroyers

The torpedo boat flotilla Flandern was founded in April 1915. The flotilla had several different tasks: to fight off enemy invasions with support from seaplanes, to provide protection against sea mines, saving pilots and staff from crashed airplanes, and they had to provide suppressive fire for German attacks aimed at enemy artillery batteries on the English and French coast. At the end of 1916, a ‘Halbflotille’ (half a flotilla) of three destroyer ships (known to the Germans as ‘zerstörers’) was created. Some time later a second ‘Halbflotille’ would be made. The destroyers were supposed to clear out the mine fields and submarine nets, which were lethal to the submarines. In order to track down and disarm enemy mines, a specialized ‘Halbflotille’ was created. This special unit consisted of a large variety of vehicles like fishing boats and older torpedo boats.

Charles Fryatt’s Golden Watches

Thousands of ships and crewmembers were lost during the First World War. One of the most famous events is how the American ocean liner Lusitania sank in 1915. Almost 1200 people died during the incident. Another story which is lesser well-known nowadays, but which used to be an infamous tale during and directly after the was, is the story about the S. S. Brussels and her captain Charles Fryatt.

Charles Fryatt (1872-1916) was a captain of a passengers ship which belonged amongt others to the Great Central Railway. These ships followed service lines and would thus travel back and forth between England and the Netherlands.

He was the captain of the S. S. Wrexham when the ship was hailed by a German submarine on March 3rd 1915. Fryatt did not hesitate and ordered to boil the water in the kettles of the ship. The Wrexham enter the port of Rotterdam with blackened funnels. Charles Fryatt received a golden watch with special inscriptions from his employer for this heroic act. He earned another golden watch later that month. On March 28th 1915, when Fryatt was the captain of passengers ship S. S. Brussels, a German submarine sailing above the waterline approached his ship. The submarine, an U-33 boat, signaled with flag to Fryatt’s ship and ordered it to stop. The event took place near a lightship located in the Maas river. Since the submarine was too close to get away, Fryatt ordered the ship to sail at full speed in an attempt to ram the U-33. The submarine, however, was still able to submerge itself in time. This time around, Fryatt received a golden watch from the British admiralty.

Brought to Bruges

A year later the Germans finally managed to capture captain Charles Fryatt. His ship the S. S. Brussels left the ‘Hoek van Holland’ on June 25th 1916 and was supposed to sail to Harwich. One of the passengers allegedly used a signaling light, on the shore signaling lights were also spotted. Five German destroyers surrounded the passengers ship. The ship was first brought to Zeebrugge and later to Bruges. The crew was transported to Rubleben, an internment camp in Germany by train. A couple of days later the army command started to realize who they managed to capture: the man who tried to sink their U-33 submarine. Fryatt was transported back to Brugge, and after a short court-martial trial on July 27th 1916, he was executed on the same day.

In a public announcement admiral Von Schröder, commander of the ‘Marine–Korps Flandern’, declared that although Charles Fryatt was not in service of the Allied Military forces, he was executed nevertheless because he had tried to sink a German submarine. The execution of Fryatt sparked uproar and international protests. The case is controversial even today. Was Charles Fryatt rightfully sentenced to death?

In the air

‘Marine–Korps Flandern’ expanded at the end of 1914 with the addition of a ‘Seeflugstation’ (seaplane station) in Zeebrugge, some time later a ‘Seeflugstation would be opened in Ostend. In 1915 two ‘Marine-Landfliegerabteilungen’ (Marine land plane departments) which were later called ‘Marine-Feldflieger’ (Marine field flyers) were introduced as well. As a consequence of the increasing amount of aerial vehicles, multiple airfield were build behind the Flemish coastal region.

The airplanes had several tasks: reconnaissance, defending the fleet, attacking enemy vehicles and bombing England. Reconnaissance missions and bombings were also done by airships.

The Allied forces attacked ‘Marine–Korps Flandern’ from Zeeuws-Vlaanderen. Flight paths were located above Western Zeeuws-Vlaanderen. Air battles often took place above Dutch territory. Moreover, many planes crashed in the region of Cadzand.

Battle of the Somme, 1916

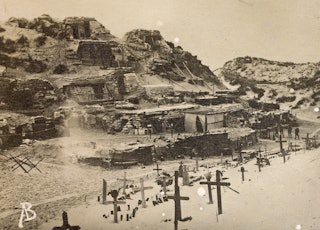

Soldiers of the ‘Marine–Korps Flandern’ also fought in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. The Allied forces attacked the German trenches near the river Somme, located 100 kilometers north of Paris, marking a triangular territory between the French cities of Albert, Bapaume and Péronne, on June 25th 1916. Their plan – to force a decisive breakthrough in the overly static trench warfare – failed miserably. Despite enormous losses the British continued their attacks. In this battle, Allied forces used tanks for the first time during a war. The battle did not end until November 18th 1916. Many lives were lost: 420.000 soldiers from the United Kingdom, 200.000 French soldiers and 450.000 German soldiers had died. [2]

Allied attacks on the Flemish coast

The part of the Flemish coast, which was occupied by the ‘Marine–Korps Flandern’, had a major strategical importance because it was close to the English Channel and Great Britain. Therefore the Allied forces continually attacked the area during the war.

Operations Hush and Strandfest

During the months of July-August 1917, the British prepared an amphibious invasion. Prior to this, they carried out artillery attacks from Newport and from the river ‘Yser’. This so-called operation ‘Hush’ required a lot of communication between the Allied armies and took a long time to organize. During preparations in June 1917, however, eleven British soldier were captured by the Germans. The Germans became suspicious and started to develop a counterattack: Unternehmen Strandfest. On July 10th 1917, they attacked the narrow strip of land on the eastern bank of the ‘Yser’ from Lombardsijde. German planes bombarded the area. Torpedo boats would have provided covering fire from the seaside, and weather permitting. Eventually the Germans were able to successfully capture the British trenches near the ‘Yser’. Hundreds of British soldiers were taken to Bruges and Ostend as prisoners of war.

Third battle of Ypres – Flandernschlacht

The Allied forces tried to recapture Ostend and Zeebrugge from the mainland starting July 31st until November 11th 1917 during the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (or as the Germans call it the Flandernschlacht). The preceding artillery fire transformed the battlefield into a pool of mud. The battle lasted for a hundred days and resulted in approximately 500.000 casualties. The area of eight kilometers which was recaptured by the Allied forces was, however, strategically useless.

The Assault on Zeebrugge and Ostend 1918

The assault on Zeebrugge and Ostend on April 23rd 1918 was supposed to block the German ports and to make these inoperable for submarines and other warships. A previous attack, which was scheduled in April, was canceled due to bad weather conditions. During this operation, the Germans had captured an English ship, including their plan of attack. As a result, the Germans anticipated the attack by the Allied forces. The attack started in Dover, Dunkirk and the ‘Zwin’ in Knokke on April 23rd. Close to midnight, the Allied forces started a diversion. A smoke-screen was used to enable the HMS Vindictive and their other two ships to attack the port of Zeebrugge. The British successfully crashed a submarine loaded with explosives into the port. Their smoke-screen, however, had disappeared due to a change in wind directions. This enabled the Germans to aim and fire at the British.

While the German counter-attack focused on this assault, the British forces sank several ships loaded with concrete in front of the sluice gates. Moreover, three ships from 1890, the Thetis, Intrepid and Iphigenia, were filled with concrete. The British intended to sink these ships in the navigation channel, and as a result the ships would block the port. After the failed assault on the pier, the Germans opened fire on the three ships. The Thetis did not make it to the navigation channel but got stuck in the shallows and sank too early. The other two ships managed to reach the canal, but did not sink at the right places.

De attack on the port of Ostend, which took place at the same time, was also a failure. A second attack on Ostend in May failed too. During this second attack, the HMS Vindictive sank as well after it got stuck on the shallows near the port of Ostend. German submarines could still access the sea from Bruges, after which they would sail to either Zeebrugge or Ostend. This ended, however, in October 1918 when the British army recaptured the area.

Albums of the ‘Marine-Korps Flandern’ online

The photographs on this webpage originally belong to the collection of notary Arend Mijs (1866-1934), vice-consul of Belgium in Oostburg. The collection contains two albums filled with photographs featuring the ‘Marine-Korps Flandern’. Both albums are available online though the archive inventory Collection A. Mijs, inventory numbers 2 and 3.

www.archieven.nlPhotographs of ‘Marine-Korps Flandern’ per subject

View the photographs of ‘Marine-Korps Flandern’ per subject.

www.archieven.nlNotes

- [1] Blumenfeld, E., ‘Spiegelbeeld’ (De Harmonie 1980), p.241

- [2] Bron: Wikipedia http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slag_aan_de_Somme

- [3] Bron: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aanval_op_de_haven_van_Zeebrugge